Why are borders relevant to conflict research?

Three important issues must be considered:

1. Borders change over time

2. Borders appear and disappear over time

3. Not all borders are created equal

The map animation above illustrates the first two issues. It represents border changes to all states from 1946 - 2004 (the map is zoomed in on Africa, Europe and Asia to show some of the details).

In order to produce this animation, separate maps were created for all states across the temporal domain: extensive analysis was made

of border changes by consulting many sources in the literature, plus hundreds of maps and atlases. Not surprisingly, this presents a number of issues.

One such issue is this: when the border between two states has not been delimited, delineated or demarcated, how do we draw the line on the map?

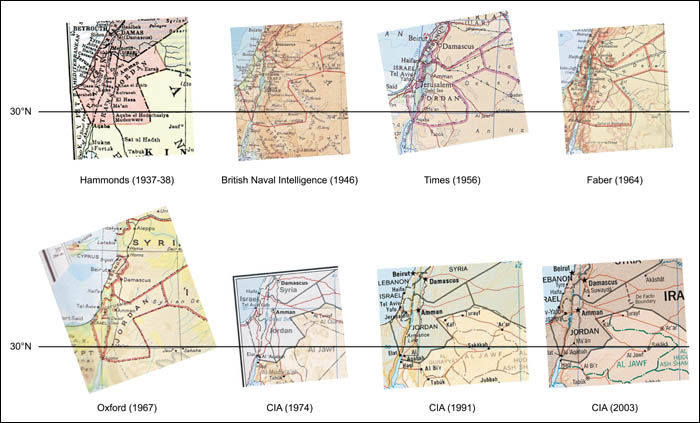

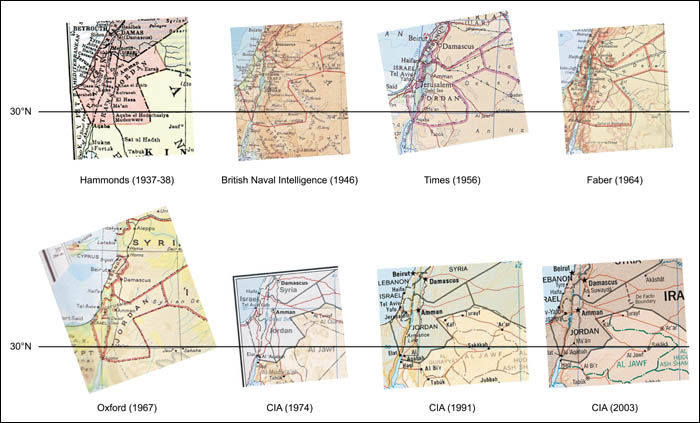

In such instances, it is necessary to consult as many maps as possible. However, this too presents difficulties. Different maps will present different borders, as can be seen in the eight maps showing the Jordan-Saudi border, below:

Starting with the first map, we can describe the

southerly border of Jordan as originating in the Gulf of Aqaba (just south of the port itself) and

continuing along the parallel. It continues until

approximately 38 deg E, at which point it turns perpendicular, heading north to the 30th parallel. There

may be a small kink in the border before it heads north; this may, however, be down to imprecision

of the map. The British Naval Intelligence map (1946) gives us a broadly similar (though more

detailed picture), except that from Aqaba, the line heads slightly south to an arbitrary point

(approximately 36 deg E), at which it continues once more until approximately 38 deg E, returning to the

same latitude as Aqaba. The picture is similar with the Times (1956) map, only mapping

inaccuracies make the diagonal lines appear to be almost curved. Immediately north of the 30th

parallel, the picture has changed: while on the previous two maps the border heads north-west, the

Times map has the border head north then north-west. Faber (1964) draws the lines more clearly,

but the angle of the lines south of the 30th parallel is less pronounced. Like the Times, the Faber

map heads north then northwest above the parallel. The Oxford (1967) map, published a year after

the border change, returns us to the borders represented by the British Naval Intelligence map,

albeit more simplified. Finally, the three CIA maps give us the border as it is recognised today:

very much different south, and indeed north, of the 30th parallel.

When borders have not been demarcated, it may be the case that the Westphalian notion of the state is not the most appropriate

lens through which to understand territorial sovereignty. Yet maps do make the Westphalian assumption and today, computer based maps

depend on it more than paper based ones. This is unfortunate, as when we ask the metaphysical question of "what do we mean by 'border'?"

we find that Westphalian border lines are only one type of border amongst many.

What do we mean by "border"?

This is a deceptively simple question. A straightforward answer would be "a border is a

thing which separates this from that." This is quite true. But it ignores the fact that, at least for

states, borders come literally in different shapes and sizes. Some states "change" as they approach

their borders: some become more physically apparent (through walls), while others just fade away.

Some states have buffer zones after their borders; some have buffer zones within their borders.

Some borders are more permeable than others. Some borders are considered "natural" (bona fide) while others

are "artificial" (fiat).

There is not enough room here to look at these issues in depth. However, from the perspective of conflict research, a concluding

remark should be made: while a cartographer may have used the same pen to draw all the world's borders, that does not mean that

they all have the same meaning.

but he does do

but he does do